Bearing Fruit in Due Season: "Flourishing" According to the Ancient Greeks

by Christopher Blackwell

Christopher Blackwell is the Louis G. Forgione University Professor of Classics at Furman University. He earned a B.A. in Classics, summa cum laude, from Marlboro College in Vermont, and a Ph.D. in Classics from Duke University. He has written books on ancient Greek history, classical Athenian democracy, and Alexander the Great. With his collaborator Neel Smith he is the developer of the CITE Architecture and Canonical Text Services, technologies for building scholarly digital libraries. With Neel Smith he is Project Architect of the Homer Multitext, a project of the Center for Hellenic Studies of Harvard University, Casey Dué and Mary Ebbott, edd.

This piece was originally presented as reflection during a regular meeting of Capita’s Board of Directors.

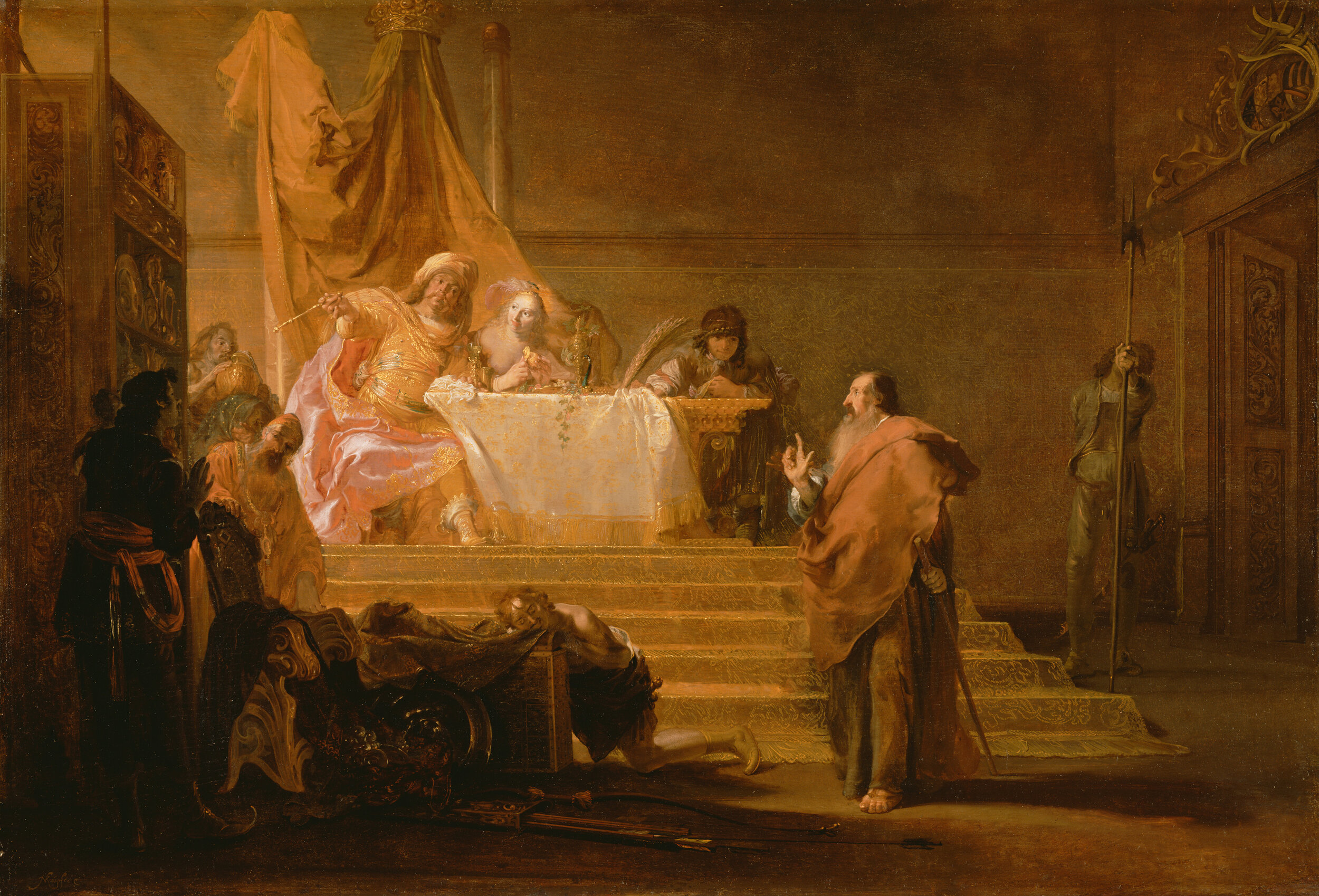

Nikolaus Knüpfer (Dutch, about 1603 - 1655)

Solon before Croesus, about 1650–1652, Oil on panel

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Our verb “to flourish” long ago ran away from its botanical etymology. But we can see it in the earliest use that I could find, from 1340 CE, when the English hermit, mystic, and prolific writer Richard Rolle of Hampole wrote of a human life, “Arely a man passes als þe gres, He floresshe and passes away.” (“Quickly a man passes all the stages, He flourishes and passes away.”) [1]

To “flourish” is to flower, but of course the point of flowers is that they pass away; we care about what comes next, for better or worse… when the cherry blossoms pass we get cherries, but anyone who has Azaleas knows that the “passing away” can be unsightly and, literally, fruitless.

The ancient Greeks knew this about “flourishing”. They tended not to speak in terms of flowers as much as in terms of leaves. The Homeric hero Glaucon, when asked about his ancestors (in the middle of a battle) says,

“Why ask of my lineage? The generations of people are like generations of leaves. The wind scatters leaves on the forest floor, but in springtime the forest, as it flourishes, [τηλεθάω] makes more.”

“Why ask of my lineage? The generations of people are like generations of leaves. The wind scatters leaves on the forest floor, but in springtime the forest, as it flourishes, [τηλεθάω] makes more.” [2]

If you are at a museum that has painted Greek pottery, look for leafy trees framing the human figures depicted; those leafy trees are icons of mortality, because every ancient Greek person knew about that speech by Glaucon in the Iliad!

In Glaucon’s view, it is not the individuals, the leaves, but the tree, or rather the forest, that flourishes, year after year in due season.

I think we can understand this better by looking at my absolute favorite story from ancient Greek literature. In Book 1 of Herodotus’ history of the war between the Greeks and the Persian Empire, he tells of how Solon the Athenian came to visit Croesus.

Croesus was King of Lydia, a vastly wealthy empire in what is now central Turkey. His name lives on in the expression “Rich as Croesus.”[3] Solon, famous for his wisdom, arrived as a tourist in Sardis, Croesus’ capital city, when that kingdom was “at the acme of wealth” (ἀκμαζούσας πλούτῳ) (Hdt. 1.29). The king entertained him as an honored guest, gave him a tour of the royal treasuries, and then, fishing for a compliment, asked him, “Have you ever known one person who was the most blessed of all?”

Solon answered, immediately, “Tellus the Athenian”. For the record, no one had ever, or has ever, heard of “Tellus the Athenian” apart from this story. Croesus demanded to know why “Joe-blow Athenian” was more blessed than he, with all his wealth and power. Solon explained:

“Tellus, in the first place, lived in a prosperous city; he had good children and saw them to grow up and have children of their own, and all of them lived to grow up. He had a good living, by our standards. And the end of his life was glorious, because in a war between his Athenian people and their neighbors in Eleusis, he led a charge, routed the enemy, and died in battle; the Athenians buried him where he fell, at public expense, and with great honors.”

“ Tellus’ good fortune was to live in a prosperous city, to prosper in his family, to enjoy sufficient material wealth, to serve and continue to serve until the very end, and to be recognized for having done so.”

For Solon, at least in this apocryphal story, “blessedness” is not determined by a momentary (and passing) “flowering” of individual prosperity, but can be identified only in a holistic view of a life, in its social context, up to and including the very end. Tellus’ good fortune was to live in a prosperous city, to prosper in his family, to enjoy sufficient material wealth, to serve and continue to serve until the very end, and to be recognized for having done so.

Glaucon in the Iliad says that it is the forest that flourishes, and Solon’s story contains implicit praise for the city of Athens as a community in which Tellus could live the most blessed life.

“We should avoid assuming that education, alone, an investment in a future community, will be sufficient to secure a good life. We can’t push the problem down the road. We, right now, are the forest, and it is up to us to provide an environment in which the Telluses of the future can live, thrive, bear fruit, and die well.”

But Solon is not a Communist! His story does not subordinate the individual Tellus to some collective good. Tellus was blessed in his community, and seen to be blessed because he raised his family successfully, and chose to serve his country, and did so with martial skill and courage, and paid the ultimate price.

The story in Herodotus cannot possibly be historically factual (Solon probably died in in 560 BCE, and Croesus only became king of Lydia in 560). But it is true in the sense that matters.

A “good life”—which Herodotus calls a “blessed” life—is a matter of flowering, and bearing fruit, and dying, well and in due season, in a flourishing forest.

When we talk about education, it is invariably valued for its ability to enhance our communities and our society. When we see our society falling short of our ideals, our instinct (which is correct) is to improve education, hoping that tomorrow’s citizens will make a better world. It is possible, though, that we are committing an error that is the inverse of the error of Croesus.

He saw his own, personal, present wealth as proof of his blessedness. This was a mistake (Cyrus the Great of Persia, soon thereafter, conquered Lydia).

We should avoid assuming that education, alone, an investment in a future community, will be sufficient to secure a good life. We can’t push the problem down the road. We, right now, are the forest, and it is up to us to provide an environment in which the Telluses of the future can live, thrive, bear fruit, and die well.

[1] Richard Rolle, Pricke of Conscience 725.

[2] Iliad 6.145–6.150.

[3] Croesus, who was as rich as Croesus, lived in a good neighborhood. The neighboring kingdom of Phrygia was ruled by Midas, of the “Midas Touch”.